The Blessed Eucharist as a Sacrament

Since Christ is present under

the

appearances of bread and wine

in a sacramental way, the Blessed Eucharist

is

unquestionably a sacrament of the Church.

Indeed, in the Eucharist the

definition

of a Christian sacrament as

"an outward sign of an inward grace

instituted by Christ" is verified.

The investigation into the precise nature of

the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar, whose existence Protestants do not deny, is

beset with a number of difficulties. Its essence certainly does not consist in

the Consecration or the Communion, the former being merely the sacrificial

action, the latter the reception of the sacrament, and not the sacrament

itself. The question may eventually be reduced to this whether or not the

sacramentality is to be sought for in the Eucharistic species or in the Body

and Blood of Christ hidden beneath them.

The majority of theologians rightly

respond to the query by saying, that neither the species themselves nor the

Body and Blood of Christ by themselves, but the union of both factors

constitute the moral whole of the Sacrament of the Altar.

The species

undoubtedly belong to the essence of the sacrament, since it is by means of

them, and not by means of the invisible Body of Christ, that the Eucharist

possesses the outward sign of the sacrament. Equally certain is it, that the

Body and the Blood of Christ belong to the concept of the essence, because it

is not the mere unsubstantial appearances which are given for the food of our

souls but Christ concealed beneath the appearances.

The twofold number of the

Eucharistic elements of bread and wine does not interfere with the unity of the

sacrament; for the idea of refection embraces both eating and drinking, nor do

our meals in consequence double their number.

In the doctrine of the Holy

Sacrifice of the Mass, there is a question of even higher relation, in that the

separated species of bread and wine also represent the mystical separation of

Christ's Body and Blood or the unbloody Sacrifice of the Eucharistic Lamb. The

Sacrament of the Altar may be regarded under the same aspects as the other

sacraments, provided only it be ever kept in view that the Eucharist is a

permanent sacrament. Every sacrament may be considered either in itself or with

reference to the persons whom it concerns.

Passing over the Institution, which is

discussed elsewhere in connection with the words of Institution, the only

essentially important points remaining are the outward sign (matter and form)

and inward grace (effects of Communion), to which may be added the necessity of

Communion for salvation.

In regard to the persons concerned, we distinguish

between the minister of the Eucharist and its recipient or subject.

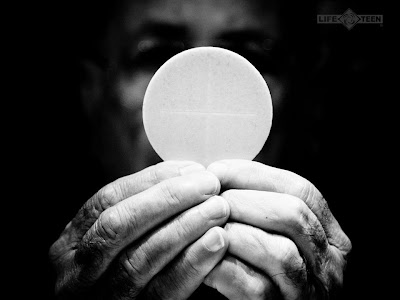

The matter or Eucharistic

elements

There are two Eucharistic

elements, bread and wine, which constitute the remote matter of the Sacrament

of the Altar, while the proximate matter can be none other than the Eucharistic

appearances under which the Body and Blood of Christ are truly present.

Bread

The first element is wheaten

bread (panis triticeus), without which the "confection of the Sacrament

does not take place" (Missale Romanum: De defectibus, sect. 3), Being true

bread, the Host must be baked, since mere flour is not bread.

Since, moreover,

the bread required is that formed of wheaten flour, not every kind of flour is

allowed for validity, such, e.g., as is ground from rye, oats, barley, Indian

corn or maize, though these are all botanically classified as grain

(frumentum).

On the other hand, the different varieties of wheat (as spelt,

amel-corn, etc.) are valid, inasmuch as they can be proved botanically to be

genuine wheat. The necessity of wheaten bread is deduced immediately from the

words of Institution: "The Lord took bread" (ton arton), in

connection with which it may be remarked, that in Scripture bread (artos),

without any qualifying addition, always signifies wheaten bread.

No doubt, too,

Christ adhered unconditionally

to the Jewish custom of using only wheaten bread

in the Passover Supper, and by the words,

"Do this for a commemoration of

me",

commanded its use for all succeeding times.

In addition to this,

uninterrupted tradition, whether it be the testimony of the Fathers or the

practice of the Church, shows wheaten bread to have played such an essential

part, that even Protestants would be loath to regard rye bread or barley bread

as a proper element for the celebration of the Lord's Supper.

The Church maintains an easier position in the

controversy respecting the use of fermented or unfermented bread. By leavened

bread (fermentum, zymos) is meant such wheaten bread as requires leaven or

yeast in its preparation and baking, while unleavened bread (azyma, azymon) is

formed from a mixture of wheaten flour and water, which has been kneaded to

dough and then baked.

After the Greek Patriarch Michael Cærularius of

Constantinople had sought in 1053 to palliate the renewed rupture with Rome by

means of the controversy, concerning unleavened bread, the two Churches, in the

Decree of Union at Florence, in 1439, came to the unanimous dogmatic decision,

that the distinction between leavened and unleavened bread did not interfere

with the confection of the sacrament, though for just reasons based upon the

Church's discipline and practice, the Latins were obliged to retain unleavened

bread, while the Greeks still held on to the use of leavened (cf, Denzinger, Enchirid.,

Freiburg, 1908, no, 692.)

Since the Schismatics had before the Council of

Florence entertained doubts as to the validity of the Latin custom, a brief

defense of the use of unleavened bread will not be out of place here.

Pope Leo

IX had as early as 1054 issued a protest against Michael Cærularius (cf. Migne,

P.L., CXLIII, 775), in which he referred to the Scriptural fact, that according

to the three Synoptics the Last Supper was celebrated "on the first day of

the azymes" and so the custom of the Western Church received its solemn

sanction from the example of Christ Himself.

The Jews, moreover, were

accustomed even the day before the fourteenth of Nisan to get rid of all the

leaven which chanced to be in their dwellings, that so they might from that time

on partake exclusively of the so-called mazzoth as bread.

As regards tradition,

it is not for us to settle the dispute of learned authorities, as to whether or

not in the first six or eight centuries the Latins also celebrated Mass with

leavened bread (Sirmond, Döllinger, Kraus) or have observed the present custom

ever since the time of the Apostles (Mabillon, Probst). Against the Greeks it

suffices to call attention to the historical fact that in the Orient the

Maronites and Armenians have used unleavened bread from time immemorial, and

that according to Origen (Commentary on Matthew, XII.6) the people of the East

"sometimes", therefore not as a rule, made use of leavened bread in

their Liturgy.

Besides, there is considerable force in the theological argument

that the fermenting process with yeast and other leaven, does not affect the

substance of the bread, but merely its quality. The reasons of congruity

advanced by the Greeks in behalf of leavened bread, which would have us

consider it as a beautiful symbol of the hypostatic union, as well as an

attractive representation of the savor of this heavenly Food, will be most

willingly accepted, provided only that due consideration be given to the

grounds of propriety set forth by the Latins with

St. Thomas Aquinas (III:74:4)

namely,

the example of Christ,

the aptitude of unleavened bread

to be regarded

as

a symbol of the purity

of His Sacred Body,

free from all corruption of sin,

and finally the instruction of St. Paul (1 Corinthians 5:8)

to keep the Pasch

not

with the leaven of malice and wickedness,

but with the unleavened bread of

sincerity and truth".

Wine

The second Eucharistic element

required is wine of the grape (vinum de vite). Hence are excluded as invalid,

not only the juices extracted and prepared from other fruits (as cider and

perry), but also the so-called artificial wines, even if their chemical constitution

is identical with the genuine juice of the grape.

The second Eucharistic element

required is wine of the grape (vinum de vite). Hence are excluded as invalid,

not only the juices extracted and prepared from other fruits (as cider and

perry), but also the so-called artificial wines, even if their chemical constitution

is identical with the genuine juice of the grape.

The necessity of wine of the

grape is not so much the result of the authoritative decision of the Church, as

it is presupposed by her (Council of Trent, Sess. XIII, cap. iv), and

is based

upon the example and

command of Christ, Who at the Last Supper

certainly

converted the natural wine of grapes

into His Blood.

This is deduced partly

from the rite of the Passover,

which required the head of the family to pass

around the

"cup of benediction" (calix benedictionis)

containing the

wine of grapes, partly, and especially,

from the express declaration of Christ,

that henceforth He would not drink

of the "fruit of the vine"

(genimen vitis).

The Catholic Church is aware of no other tradition and in this

respect she has ever been one with the Greeks. The ancient Hydroparastatæ, or

Aquarians, who used water instead of wine, were heretics in her eyes. The

counter-argument of Ad. Harnack ["Texte und Untersuchungen", new

series, VII, 2 (1891), 115 sqq.], that the most ancient of Churches was

indifferent as to the use of wine, and more concerned with the action of eating

and drinking than with the elements of bread and wine, loses all its force in

view not only of the earliest literature on the subject (the Didache, Ignatius,

Justin, Irenæus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Hippolytus, Tertullian, and

Cyprian), but also of non-Catholic and apocryphal writings, which bear

testimony to the use of bread and wine as the only and necessary elements of

the Blessed Sacrament.

On the other hand, a very ancient law of the Church

which, however, has nothing to do with the validity of the sacrament,

prescribes that a little water be added to the wine before the Consecration

(Decr. pro Armenis: aqua modicissima), a practice, whose legitimacy the Council

of Trent (Sess. XXII, can. ix) established under pain of anathema.

The rigor of

this law of the Church may be traced to the ancient custom of the Romans and

Jews, who mixed water with the strong southern wines (see Proverbs 9:2), to the

expression of calix mixtus found in Justin (First Apology 65), Irenæus (Against

Heresies V.2.3), and Cyprian (Epistle 63, no. 13 sq.), and especially to the

deep symbolical meaning contained in the mingling, inasmuch as thereby are

represented the flowing of blood and water from the side of the Crucified

Savior and the intimate union of the faithful with Christ (cf. Council of

Trent, Sess. XXII, cap. vii).

The sacramental form or the

words of consecration

In proceeding to verify the form,

which is always made up of words, we may start from the dubitable fact, that

Christ did not consecrate

by the mere fiat of His omnipotence, which found no

expression in articulate utterance, but by pronouncing the words of

Institution:

"This is my body . . . this is my blood",

and that by

the addition: "Do this for a commemoration of me".

He commanded the

Apostles to follow His example.

Were the words of Institution a mere

declarative utterance of the conversion, which might have taken place in the

"benediction" unannounced and articulately unexpressed, the Apostles

and their successors would, according to Christ's example and mandate, have

been obliged to consecrate in this mute manner also, a consequence which is

altogether at variance with the deposit of faith.

It is true, that Pope

Innocent III (De Sacro altaris myst., IV, vi) before his elevation to the

pontificate did hold the opinion, which later theologians branded as

"temerarious", that Christ consecrated without words by means of the

mere "benediction". Not many theologians, however, followed him in

this regard, among the few being Ambrose Catharinus, Cheffontaines, and Hoppe,

by far the greater number preferring to stand by the unanimous testimony of the

Fathers.

Meanwhile, Innocent III also insisted most urgently that at least in

the case of the celebrating priest, the words of Institution were prescribed as

the sacramental form.

It was, moreover, not until its comparatively recent

adherence in the seventeenth century to the famous "Confessio fidei orthodoxa"

of Peter Mogilas (cf. Kimmel, "Monum. fidei eccl. orient.", Jena,

1850, I, p. 180), that the Schismatical Greek Church adopted the view,

according to which the priest does not at all consecrate by virtue of the words

of Institution, but only by means of the Epiklesis occurring shortly after them

and expressing in the Oriental Liturgies a petition to the Holy Spirit,

"that the bread and wine may be converted into the Body and Blood of

Christ". Were the Greeks justified in maintaining this position, the immediate

result would be, that the Latins who have no such thing as the Epiklesis in

their present Liturgy, would possess neither the true Sacrifice of the Mass nor

the Holy Eucharist.

Fortunately, however, the Greeks can be shown the error of

their ways from their own writings, since it can be proved, that they

themselves formerly placed the form of Transubstantiation in the words of

Institution. Not only did such renowned Fathers as Justin (First Apology 66),

Irenæus (Against Heresies V.2.3), Gregory of Nyssa (The Great Catechism, no.

37), Chrysostom (Hom. i, de prod. Judæ, n. 6), and John Damascene (Exposition

of the Faith IV.13) hold this view, but the ancient Greek Liturgies bear

testimony to it, so that Cardinal Bessarion in 1439 at Florence called the

attention of his fellow-countrymen to the fact, that as soon as the words of

Institution have been pronounced, supreme homage and adoration are due to the

Holy Eucharist, even though the famous Epiklesis follows some time after.

The objection that the mere

historical recitation of the words of Institution taken from the narrative of

the Last Supper possesses no intrinsic consecratory force, would be well

founded, did the priest of the Latin Church merely intend by means of them to

narrate some historical event rather than pronounce them with the practical

purpose of effecting the conversion, or if he pronounced them in his own name

and person instead of the Person of Christ, whose minister and instrumental

cause he is.

Neither of the two suppositions holds in the case of a priest who

really intends to celebrate Mass. Hence, though the Greeks may in the best of

faith go on erroneously maintaining that they consecrate exclusively in their

Epiklesis, they do, nevertheless, as in the case of the Latins, actually

consecrate by means of the words of Institution contained in their Liturgies,

if Christ has instituted these words as the words of consecration and the form

of the sacrament.

We may in fact go a step farther and assert,

that the words

of Institution constitute

the only and wholly adequate

form of the Eucharist

and

that, consequently, the words of the

Epiklesis possess no inherent

consecratory value.

|

| Christ with Eucharist Vicente Juan Masip 16th Century |

The contention that the words of the Epiklesis have joint

essential value and constitute the partial form of the sacrament, was indeed

supported by individual Latin theologians, as Touttée, Renaudot, and Lebrun.

Though this opinion cannot be condemned as erroneous in faith, since it allows

to the words of Institution their essential, though partial, consecratory

value, appears nevertheless to be intrinsically repugnant.

For, since the act

of Consecration cannot remain, as it were, in a state of suspense, but is

completed in an instant of time, there arises the dilemma: Either the words of

Institution alone and, therefore, not the Epiklesis, are productive of the

conversion, or the words of the Epiklesis alone have such power and not the

words of Institution.

Of more considerable importance is the circumstance that

the whole question came up for discussion in the council for union held at

Florence in 1439. Pope Eugene IV urged the Greeks to come to a unanimous

agreement with the Roman faith and subscribe to the words of Institution as

alone constituting the sacramental form, and to drop the contention that the words

of the Epiklesis also possessed a partial consecratory force.

But when the

Greeks, not without foundation, pleaded that a dogmatic decision would reflect

with shame upon their whole ecclesiastical past, the ecumenical synod was

satisfied with the oral declaration of Cardinal Bessarion recorded in the

minutes of the council for 5 July, 1439 (P.G., CLXI, 491), namely, that the

Greeks follow the universal teaching of the Fathers, especially of

"blessed John Chrysostom, familiarly known to us", according to whom

the

"Divine words of Our Redeemer

contain the full and entire force of

Transubstantiation".

The venerable antiquity of the Oriental

Epiklesis, its peculiar position in the Canon of the Mass, and its interior

spiritual unction, oblige the theologian to determine its dogmatic value and to

account for its use. Take, for instance, the Epiklesis of the Ethiopian

Liturgy: "We implore and beseech Thee, O Lord, to send forth the Holy

Spirit and His Power upon this Bread and Chalice and convert them into the Body

and Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ."

Since this prayer always follows

after the words of Institution have been pronounced, the theological question

arises, as to how it may be made to harmonize with the words of Christ, which

alone possess the consecrated power.

Two explanations have been suggested

which, however, can be merged in one. The first view considers the Epiklesis to

be a mere declaration of the fact, that the conversion has already taken place,

and that in the conversion just as essential a part is to be attributed to the

Holy Spirit as Co-Consecrator as in the allied mystery of the Incarnation.

Since, however, because of the brevity of the actual instant of conversion, the

part taken by the Holy Spirit could not be expressed, the Epiklesis takes us

back in imagination to the precious moment and regards the Consecration as just

about to occur.

A similar purely psychological retrospective transfer is met

with in other portions of the Liturgy, as in the Mass for the Dead, wherein the

Church prays for the departed as if they were still upon their bed of agony and

could still be rescued from the gates of hell.

Thus considered, the Epiklesis

refers us back to the Consecration as the center about which all the

significance contained in its words revolves.

A second explanation is based,

not upon the enacted Consecration, but upon the approaching Communion, inasmuch

as the latter, being the effective means of uniting us more closely in the

organized body of the Church, brings forth in our hearts the mystical Christ,

as is read in the Roman Canon of the Mass: "Ut nobis corpus et sanguis

fiat", i.e. that it may be made for us the body and blood.

It was in this

purely mystical manner that the Greeks themselves explained the meaning of the

Epiklesis at the Council of Florence (Mansi, Collect. Concil., XXXI, 106).

Yet

since much more is contained in the plain words than this true and deep

mysticism, it is desirable to combine both explanations into one, and so we

regard the Epiklesis, both in point of liturgy and of time, as the significant

connecting link, placed midway between the Consecration and the Communion in

order to emphasize the part taken by the Holy Spirit in the Consecration of

bread and wine, and, on the other hand, with the help of the same Holy Spirit

to obtain the realization of the true Presence of the Body and Blood of Christ

by their fruitful effects on both priest and people.

The effects of the holy

Eucharist

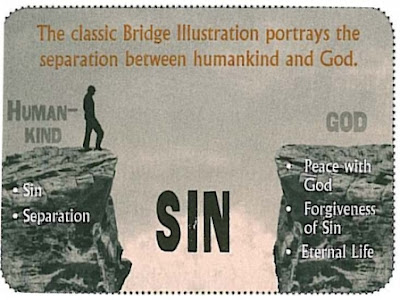

The doctrine of the Church

regarding the effects or the fruits of Holy Communion centers around two ideas:

(a) the union with Christ by love and (b) the spiritual repast of the soul.

Both ideas are often verified in one and same effect of Holy Communion.

The union with Christ by

love

The first and principal effect of

the Holy Eucharist is union with Christ by love (Decr. pro Armenis: adunatio ad

Christum), which union as such does not consist in the sacramental reception of

the Host, but in the spiritual and mystical union with Jesus by the theological

virtue of love. Christ Himself designated the idea of Communion as a union

love: "He that eateth my flesh, and drinketh blood, abideth in me, and I

in him" (John 6:57). St. Cyril of Alexandria (Hom. in Joan., IV, xvii)

beautifully represents this mystical union as the fusion of our being into that

of the God-man, as "when melted wax is fused with other wax".

Since

the Sacrament of Love is not satisfied with an increase of habitual love only,

but tends especially to fan the flame of actual love to an intense ardor, the

Holy Eucharist is specifically distinguished from the other sacraments, and

hence it is precisely in this latter effect that Francisco Suárez, recognizes

the so-called "grace of the sacrament", which otherwise is so hard to

discern. It stands to reason that the essence of this union by love consists

neither in a natural union with Jesus analogous to that between soul and body,

nor in a hypostatic union of the soul with the Person of the Word, nor finally

in a pantheistical deification of the communicant, but simply in a moral but

wonderful union with Christ by the bond of the most ardent charity.

Hence the

chief effect

of a worthy Communion

is to a certain extent a foretaste of

heaven,

in fact the anticipation and pledge of our future union with God by

love in the Beatific Vision. He alone can properly estimate the precious boon

which Catholics possess in the Holy Eucharist, who knows how to ponder these

ideas of Holy Communion to their utmost depth.

The immediate result of this

union with Christ by love is the bond of charity existing between the faithful

themselves as St. Paul says: "For we being many, are one bread, one body,

all that partake of one bread" (1 Corinthians 10:17).

And so the Communion

of Saints is not merely an ideal union by faith and grace, but an eminently

real union, mysteriously constituted, maintained, and guaranteed by partaking

in common of one and the same Christ.

The spiritual repast of the

soul

A second fruit of this union with

Christ by love is an increase of sanctifying grace in the soul of the worthy

communicant.

A second fruit of this union with

Christ by love is an increase of sanctifying grace in the soul of the worthy

communicant.

Here let it be remarked at the outset, that the Holy Eucharist

does not per se constitute a person in the state of grace as do the sacraments

of the dead (baptism and penance), but presupposes such a state.

It is,

therefore, one of the sacraments of the living.

It is as impossible for the

soul

in the state of mortal sin

to receive this Heavenly Bread

with profit, as

it is for a corpse

to assimilate food and drink.

Hence the Council of Trent

(Sess. XIII. can. v), in opposition to Luther and Calvin, purposely defined,

that the "chief fruit of the Eucharist does not consist in the forgiveness

of sins".

For though Christ said of the Chalice: "This is my blood of

the new testament, which shall be shed for many unto remission of sins"

(Matthew 26:28), He had in view an effect of the sacrifice, not of the

sacrament; for He did not say that His Blood would be drunk unto remission of

sins, but shed for that purpose.

It is for this very reason that St. Paul (1

Corinthians 11:28) demands that rigorous "self-examination", in order

to avoid the heinous offense of being guilty of the Body and the Blood of the

Lord by "eating and drinking unworthily", and that the Fathers insist

upon nothing so energetically as upon a pure and innocent conscience.

In spite

of the principles just laid down, the question might be asked, if the Blessed

Sacrament could not at times per accidens free the communicant from mortal sin,

if he approached the Table of the Lord unconscious of the sinful state of his

soul. Presupposing what is self-evident, that there is question neither of a

conscious sacrilegious Communion nor a lack of imperfect contrition (attritio),

which would altogether hinder the justifying effect of the sacrament,

theologians incline to the opinion, that in such exceptional cases the

Eucharist can restore the soul to the state of grace, but all without exception

deny the possibility of the reviviscence of a sacrilegious or unfruitful

Communion after the restoration of the soul's proper moral condition has been effected,

the Eucharist being different in this respect from the sacraments which imprint

a character upon the soul (baptism, confirmation, and Holy orders).

Together

with the increase of sanctifying grace there is associated another effect,

namely, a certain spiritual relish or delight of soul (delectatio spiritualis).

Just as food and drink delight and refresh the heart of man, so does this

"Heavenly Bread containing within itself all sweetness" produce in

the soul of the devout communicant ineffable bliss, which, however, is not to

be confounded with an emotional joy of the soul or with sensible sweetness.

Although both may occur as the result of a special grace, its true nature is

manifested in a certain cheerful and willing fervor in all that regards Christ

and His Church, and in the conscious fulfillment of the duties of one's state

of life, a disposition of soul which is perfectly compatible with interior

desolation and spiritual dryness.

A good Communion is recognized less

in the

transitory sweetness of the emotions

than in its lasting practical effects

on

the conduct of our daily lives.

Forgiveness of venial sin

and preservation from mortal sin

Though Holy Communion does not

per se remit mortal sin, it has nevertheless the third effect of "blotting

out venial sin and preserving the soul from mortal sin" (Council of Trent,

Sess. XIII, cap. ii).

Though Holy Communion does not

per se remit mortal sin, it has nevertheless the third effect of "blotting

out venial sin and preserving the soul from mortal sin" (Council of Trent,

Sess. XIII, cap. ii).

The Holy Eucharist is not merely a food, but a medicine

as well. The destruction of venial sin and of all affection to it, is readily

understood on the basis of the two central ideas mentioned above.

Just as

material food banishes minor bodily weaknesses and preserves man's physical

strength from being impaired, so does this food of our souls remove our lesser

spiritual ailments and preserve us from spiritual death.

As a union based upon

love, the Holy Eucharist cleanses with its purifying flame the smallest stains

which adhere to the soul, and at the same time serves as an effective

prophylactic against grievous sin.

It only remains for us to ascertain with clearness

the manner in which this preservative influence against relapse into mortal sin

is exerted.

According to the teaching of the Roman Catechism, it is effected by

the allaying of concupiscence, which is the chief source of deadly sin,

particularly of impurity.

Therefore it is that spiritual writers

recommend

frequent Communion

as the most effective remedy against impurity,

since its

powerful influence is felt

even after other means have proved

unavailing (cf.

St. Thomas: III:79:6).

Whether or not the Holy Eucharist is directly conducive

to the remission of the temporal punishment due to sin, is disputed by St.

Thomas (III:79:5), since the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar was not instituted

as a means of satisfaction; it does, however, produce an indirect effect in

this regard, which is proportioned to the communicant's love and devotion.

The

case is different as regards the effects of grace in behalf of a third party.

The pious custom of the faithful

of "offering their Communion"

for

relations, friends, and the souls departed,

is to be considered as possessing

unquestionable value, in the first place,

because an earnest prayer of petition

in the presence of the Spouse of our souls

will readily find a hearing, and

then,

because the fruits of Communion as a

means of satisfaction for sin may

be

applied to a third person, and

especially per modum suffragii

to the souls in

purgatory.

The pledge of our

resurrection

As a last effect we may mention

that the Eucharist is the "pledge of our glorious resurrection and eternal

happiness" (Council of Trent, Sess. XIII, cap. ii), according to the

promise of Christ: "He that eateth my flesh and drinketh my blood, hath

everlasting life: and I will raise him up on the last day." Hence the

chief reason why the ancient Fathers, as Ignatius (Letter to the Ephesians 20),

Irenæus (Against Heresies IV.18.4), and Tertullian (On the Resurrection of the

Flesh 8), as well as later patristic writers, insisted so strongly upon our

future resurrection, was the circumstance that it is the door by which we enter

upon unending happiness.

As a last effect we may mention

that the Eucharist is the "pledge of our glorious resurrection and eternal

happiness" (Council of Trent, Sess. XIII, cap. ii), according to the

promise of Christ: "He that eateth my flesh and drinketh my blood, hath

everlasting life: and I will raise him up on the last day." Hence the

chief reason why the ancient Fathers, as Ignatius (Letter to the Ephesians 20),

Irenæus (Against Heresies IV.18.4), and Tertullian (On the Resurrection of the

Flesh 8), as well as later patristic writers, insisted so strongly upon our

future resurrection, was the circumstance that it is the door by which we enter

upon unending happiness.

There can be nothing incongruous or improper in the

fact that the body also shares in this effect of Communion, since by its

physical contact with the Eucharist species, and hence (indirectly) with the

living Flesh of Christ, it acquires a moral right to its future resurrection,

even as the Blessed Mother of God, inasmuch as she was the former abode of the

Word made flesh, acquired a moral claim to her own bodily assumption into

heaven.

The further discussion as to whether some "physical quality"

(Contenson) or a "sort of germ of immortality" (Heimbucher) is

implanted in the body of the communicant, has no sufficient foundation in the

teaching of the Fathers and may, therefore, be dismissed without any injury to

dogma.

The necessity of the holy

Eucharist for salvation

We distinguish two kinds of

necessity,

•the necessity of means

(necessitas medii) and

•the necessity of precept

(necessitas præcepti).

In the first sense a thing or action is

necessary because without it a given end cannot be attained; the eye, e.g. is

necessary for vision. The second sort of necessity is that which is imposed by

the free will of a superior, e.g. the necessity of fasting.

In the first sense a thing or action is

necessary because without it a given end cannot be attained; the eye, e.g. is

necessary for vision. The second sort of necessity is that which is imposed by

the free will of a superior, e.g. the necessity of fasting.

As regards

Communion a further distinction must be made between infants and adults. It is

easy to prove that in the case of infants Holy Communion is not necessary to

salvation, either as a means or as of precept. Since they have not as yet

attained to the use of reason, they are free from the obligation of positive

laws; consequently, the only question is whether Communion is, like Baptism,

necessary for them as a means of salvation. Now the Council of Trent under pain

of anathema, solemnly rejects such a necessity (Sess. XXI, can. iv) and

declares that the custom of the primitive Church of giving Holy Communion to

children was not based upon the erroneous belief of its necessity to salvation,

but upon the circumstances of the times (Sess. XXI, cap. iv).

Since according

to St. Paul's teaching (Romans 8:1) there is "no condemnation" for

those who have been baptized, every child that dies in its baptismal innocence,

even without Communion, must go straight to heaven. This latter position was

that usually taken by the Fathers, with the exception of St. Augustine, who

from the universal custom of the Communion of children drew the conclusion of

its necessity for salvation.

On the other hand, Communion

is prescribed for adults, not only by the law of the Church, but also by a

Divine command (John 6:50 sqq.), though for its absolute necessity as a means

to salvation there is no more evidence than in the case of infants. For such a

necessity could be established only on the supposition that Communion per se

constituted a person in the state of grace or that this state could not be

preserved without Communion. Neither supposition is correct. Not the first, for

the simple reason that the Blessed Eucharist, being a sacrament of the living,

presupposes the state of sanctifying grace; not the second, because in case of

necessity, such as might arise, e.g., in a long sea-voyage, the Eucharistic

graces may be supplied by actual graces.

It is only when viewed in this light

that we can understand how the primitive Church, without going counter to the

Divine command, withheld the Eucharist from certain sinners even on their

deathbeds.

There is, however, a moral necessity on the part of adults to

receive Holy Communion, as a means, for instance, of overcoming violent

temptation, or as a viaticum for persons in danger of death.

Eminent divines,

like Francisco Suárez, claim that the Eucharist, if not absolutely necessary,

is at least a relatively and morally necessary means to salvation, in the sense

that no adult can long sustain his spiritual, supernatural life who neglects on

principle to approach Holy Communion. This view is supported, not only by the

solemn and earnest words of Christ, when He Promised the Eucharist, and by the

very nature of the sacrament as the spiritual food and medicine of our souls,

but also by the fact of the helplessness and perversity of human nature and by

the daily experience of confessors and directors of souls.

Since Christ has left us no definite precept

as to the frequency with which He desired us to receive Him in Holy Communion,

it belongs to the Church to determine the Divine command more accurately and

prescribe what the limits of time shall be for the reception of the sacrament.

In the course of centuries the Church's discipline in this respect has

undergone considerable change. Whereas the early Christians were accustomed to

receive at every celebration of the Liturgy, which probably was not celebrated

daily in all places, or were in the habit of Communicating privately in their

own homes every day of the week, a falling-off in the frequency of Communion is

noticeable since the fourth century.

Even in his time Pope Fabian (236-250)

made it obligatory to approach the Holy Table three times a year, viz, at

Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, and this custom was still prevalent in the

sixth century [cf. Synod of Agde (506), c. xviii].

Although St. Augustine left

daily Communion to the free choice of the individual, his admonition, in force

even at the present day, was: Sic vive, ut quotidie possis sumere (The Gift of

Perseverance 14), i.e. "So live that you may receive every day."

From

the tenth to the thirteenth century, the practice of going to Communion more

frequently during the year was rather rare among the laity and obtained only in

cloistered communities.

St. Bonaventure reluctantly allowed the lay brothers of

his monastery to approach the Holy Table weekly, whereas the rule of the Canons

of Chrodegang prescribed this practice.

When the Fourth Council of Lateran

(1215), held under Innocent III, mitigated the former severity of the Church's

law to the extent that all Catholics of both sexes were to communicate at least

once a year and this during the paschal season, St. Thomas (III:80:10) ascribed

this ordinance chiefly to the "reign of impiety and the growing cold of

charity".

The precept of the yearly paschal Communion was solemnly

reiterated by the Council of Trent (Sess. XIII, can. ix). The mystical

theologians of the later Middle Ages, as Tauler, St. Vincent Ferrer,

Savonarola, and later on St. Philip Neri, the Jesuit Order, St. Francis de

Sales and St. Alphonsus Liguori were zealous champions of frequent Communion;

whereas the Jansenists, under the leadership of Antoine* Arnauld (De la

fréquente communion, Paris, 1643), strenuously opposed and demanded as a

condition for every Communion the "most perfect penitential dispositions

and the purest love of God". This rigorism was condemned by Pope Alexander

VIII (7 Dec., 1690); the Council of Trent (Sess. XIII, cap. viii; Sess. XXII,

cap. vi) and Innocent XI (12 Feb., 1679) had already emphasized the

permissibility of even daily Communion.

To root out the last vestiges of

Jansenistic rigorism, Pius X issued a decree (24 Dec., 1905) wherein he allows

and recommends daily Communion to the entire laity and requires but two

conditions for its permissibility, namely, the state of grace and a right and

pious intention.

Concerning the non-requirement of the twofold species as a

means necessary to salvation see COMMUNION UNDER BOTH KINDS.

The minister of the

Eucharist

The Eucharist being a permanent

sacrament, and the confection (confectio) and the reception (susceptio) thereof

being separated from each other by an interval of time, the minister may be and

in fact is twofold: (a) the minister of consecration and (b) the minister of

administration.

|

| Blessed John Paul II |

The Minister

of

Consecration

In the early Christian Era the

Peputians, Collyridians, and Montanists attributed priestly powers even to

women (cf. Epiphanius, De hær., xlix, 79); and in the Middle Ages the

Albigenses and Waldenses ascribed the power to consecrate to every layman of

upright disposition.

Against these errors

the Fourth Lateran Council (1215)

confirmed the ancient Catholic teaching,

that "no one but the priest

[sacerdos],

regularly ordained according to

the keys of the Church,

has the

power of consecrating this sacrament".

Rejecting the hierarchical

distinction between the priesthood and the laity, Luther later on declared, in

accord with his idea of a "universal priesthood" (cf. 1 Peter 2:5),

that every layman was qualified, as the appointed representative of the

faithful, to consecrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist. The Council of Trent

opposed this teaching of Luther, and not only confirmed anew the existence of a

"special priesthood" (Sess. XXIII, can. i), but authoritatively

declared that "Christ ordained the Apostles true priests and commanded

them as well as other priests to offer His Body and Blood in the Holy Sacrifice

of the Mass" (Sess. XXII, can. ii).

By this decision it was also declared

that the power of consecrating and that of offering the Holy Sacrifice are

identical. Both ideas are mutually reciprocal. To the category of

"priests" (sacerdos, iereus) belong, according to the teaching of the

Church, only bishops and priests; deacons, subdeacons, and those in minor

orders are excluded from this dignity.

Scripturally considered, the necessity of a

special priesthood with the power of validly consecrating is derived from the

fact that Christ did not address the words, "Do this", to the whole

mass of the laity, but exclusively to the Apostles and their successors in the

priesthood; hence the latter alone can validly consecrate.

It is evident that

tradition has understood the mandate of Christ in this sense and in no other.

We learn from the writings of Justin, Origen, Cyprian, Augustine, and others,

as well as from the most ancient Liturgies, that it was always the bishops and

priests, and they alone, who appeared as the property constituted celebrants of

the Eucharistic Mysteries, and that the deacons merely acted as assistants in

these functions, while the faithful participated passively therein.

When in the

fourth century the abuse crept in of priests receiving Holy Communion at the

hands of deacons, the First Council of Nicæa (325) issued a strict prohibition

to the effect, that "they who offer the Holy Sacrifice shall not receive

the Body of the Lord from the hands of those who have no such power of

offering", because such a practice is contrary to "rule and

custom".

The sect of the Luciferians was founded by an apostate deacon

named Hilary, and possessed neither bishops nor priests; wherefore St. Jerome

concluded (Dial. adv. Lucifer., n. 21), that for want of celebrants they no

longer retained the Eucharist.

It is clear that the Church has always denied

the laity the power to consecrate. When the Arians accused St. Athanasius (d.

373) of sacrilege, because supposedly at his bidding the consecrated Chalice

had been destroyed during the Mass which was being celebrated by a certain

Ischares, they had to withdraw their charges as wholly untenable when it was

proved that Ischares had been invalidly ordained by a pseudo-bishop named

Colluthos and, therefore, could neither validly consecrate nor offer the Holy

Sacrifice.

The minister of

administration

The dogmatic interest which

attaches to the minister of administration or distribution is not so great, for

the reason that the Eucharist being a permanent sacrament, any communicant

having the proper dispositions could receive it validly, whether he did so from

the hand of a priest, or layman, or woman.

The dogmatic interest which

attaches to the minister of administration or distribution is not so great, for

the reason that the Eucharist being a permanent sacrament, any communicant

having the proper dispositions could receive it validly, whether he did so from

the hand of a priest, or layman, or woman.

Hence, the question is concerned,

not with the validity, but with the liceity of administration. In this matter

the Church alone has the right to decide, and her regulations regarding the

Communion rite may vary according to the circumstances of the times. In general

it is of Divine right, that the laity should as a rule receive only from the

consecrated hand of the priest (cf. Trent, Sess. XIII, cap. viii). The practice

of the laity giving themselves Holy Communion was formerly, and is today,

allowed only in case of necessity.

In ancient Christian times it was customary

for the faithful to take the Blessed Sacrament to their homes and Communicate

privately, a practice (Tertullian, Ad uxor., II, v), to which, even as late as

the fourth century, St. Basil makes reference (Epistle 93). Up to the ninth

century, it was usual for the priest to place the Sacred Host in the right hand

of the recipient, who kissed it and then transferred it to his own mouth;

women, from the fourth century onward, were required in this ceremony to have a

cloth wrapped about their right hand. The Precious Blood was in early times

received directly from the Chalice, but in Rome the practice, after the eighth

century, was to receive it through a small tube (fistula); at present this is

observed only in the pope's Mass. The latter method of drinking the Chalice

spread to other localities, in particular to the Cistercian monasteries, where

the practice was partially continued into the eighteenth century.

Whereas the priest is both by

Divine and ecclesiastical right the ordinary dispenser (minister ordinarius) of

the sacrament, the deacon is by virtue of his order the extraordinary minister

(minister extraordinarius), yet he may not administer the sacrament except ex

delegatione, i.e. with the permission of the bishop or priest.

As has already

been mentioned above, the deacons were accustomed in the Early Church to take

the Blessed Sacrament to those who were absent from Divine service, as well as

to present the Chalice to the laity during the celebration of the Sacred

Mysteries (cf. Cyprian, Treatise 3, nos. 17 and 25), and this practice was

observed until Communion under both kinds was discontinued. In St. Thomas' time

(III:82:3), the deacons were allowed to administer only the Chalice to the

laity, and in case of necessity the Sacred Host also, at the bidding of the

bishop or priest.

After the Communion of the laity under the species of wine

had been abolished, the deacon's powers were more and more restricted.

According to a decision of the Sacred Congregation of Rites (25 Feb., 1777),

still in force, the deacon is to administer Holy Communion only in case of

necessity and with the approval of his bishop or his pastor. (Cf. Funk,

"Der Kommunionritus" in his "Kirchengeschichtl. Abhandlungen und

Untersuchungen", Paderborn, 1897, I, pp. 293 sqq.; see also "Theol.

praktische Quartalschrift", Linz, 1906, LIX, 95 sqq.)

The recipient of the

Eucharist

The two conditions of objective

capacity (capacitas, aptitudo) and subjective worthiness (dignitas) must be

carefully distinguished. Only the former is of dogmatic interest, while the

latter is treated in moral theology. The

first requisite of aptitude or capacity is that the recipient be a "human

being", since it was for mankind only that Christ instituted this

Eucharistic food of souls and commanded its reception. This condition excludes not only irrational

animals, but angels also; for neither possess human souls, which alone can be

nourished by this food unto eternal life.

The two conditions of objective

capacity (capacitas, aptitudo) and subjective worthiness (dignitas) must be

carefully distinguished. Only the former is of dogmatic interest, while the

latter is treated in moral theology. The

first requisite of aptitude or capacity is that the recipient be a "human

being", since it was for mankind only that Christ instituted this

Eucharistic food of souls and commanded its reception. This condition excludes not only irrational

animals, but angels also; for neither possess human souls, which alone can be

nourished by this food unto eternal life.

The expression "Bread of

Angels" (Psalm 77:25) is a mere metaphor, which indicates that in the

Beatific Vision where He is not concealed under the sacramental veils, the

angels spiritually feast upon the God-man, this same prospect being held out to

those who shall gloriously rise on the Last Day.

The second requisite, the immediate

deduction from the first, is that the recipient be still in the "state of

pilgrimage" to the next life (status viatoris), since it is only in the

present life that man can validly Communicate.

Exaggerating the Eucharist's

necessity as a means to salvation, Rosmini advanced the untenable opinion that

at the moment of death this heavenly food is supplied in the next world to

children who had just departed this life, and that Christ could have given

Himself in Holy Communion to the holy souls in Limbo, in order to "render

them apt for the vision of God". This evidently impossible view, together

with other propositions of Rosmini, was condemned by Leo XIII (14 Dec., 1887).

In the fourth century the Synod of Hippo (393) forbade the practice of giving

Holy Communion to the dead as a gross abuse, and assigned as a reason, that

"corpses were no longer capable of eating".

Later synods, as those of

Auxerre (578) and the Trullian (692), took very energetic measures to put a stop

to a custom so difficult to eradicate.

The third requisite, finally, is baptism,

without which no other sacrament can be validly received; for in its very

concept baptism is the "spiritual door" to the means of grace

contained in the Church.

A Jew or Mohammedan might, indeed, materially receive

the Sacred Host, but there could be no question in this case of a sacramental

reception, even though by a perfect act of contrition or of the pure love of

God he had put himself in the state of sanctifying grace. Hence in the Early

Church the catechumens were strictly excluded from the Eucharist.